In the last decade, dental implants have been widely used as a basis for removable or permanent restorations in partially or completely edentulous patients.

This trend is a result of the high success rates of both implants and implant-supported reconstruction. 1,2 With the increase in the use of implants, we are witnessing the emergence of

of new inflammatory diseases – peri-implantitis and peri-implant mucositis. The term peri-implantitis was first described in 1987 in an article by Mombelli et al.3.

The disease was defined as an inflammatory disease with characteristics similar to periodontitis. Since then, the disease has tended to be characterized as a separate entity from periodontitis.

While peri-implant mucositis is defined as an inflammatory disease limited to the soft tissue around the implant, peri-implantitis also involves the surrounding bone 4,5.

Various studies have presented different clinical and radiographic parameters for defining peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis, and there is a lack of uniform and precise criteria.

For the diagnosis of each of these diagnoses 6-10.

The currently accepted definition of peri-implantitis according to the eighth EFP consensus includes a change in the height of the crestal bone around the implant, the presence of bleeding on contact with the implant, and

Probing and/or purulent discharge with or without deepening of the peri-implant pocket11. There are varying reports regarding the incidence of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis in the literature.

In general, the incidence of peri-implantitis over 5-10 years is estimated to be 101% of implants and 201% of patients. 12-13

The incidence of peri-implant mucositis is higher – Atieh and colleagues reported a prevalence of peri-implant mucositis in 63.41% of patients.

In the same study, when considering the implant as the statistical unit, peri-implant mucositis was found in 30.71% of patients. The high variability in reporting the incidence of peri-implantitis

May be the result of a different definition of the disease (different threshold of bone loss, differences in defining the presence of inflammatory parameters – BOP, PD and their combination)

and/or different follow-up times. In addition, the sample population differs in the different studies.

Etiology

Peri-implant diseases are caused in response to the presence of peri-pathogenic bacteria on the implant surface, similar to their colonization on the tooth surface.

Their accumulation leads to the stimulation and activation of inflammatory mediators that are part of the patient's immune system, which causes a reaction that destroys the implant's attachment tissues15.

The inflammatory process in peri-implant mucositis is similar to the inflammatory process that occurs around teeth in gingivitis. The structure of the epithelial barrier around teeth and implants

(Junctional epithelium and barrier epithelium, respectively) are similar, although their developmental origins are different. Connective tissue, unlike epithelium,

It has a different structure and composition in the gums around teeth and in the mucosa around implants. Around implants, the mucosa contains more collagen and fewer fibroblasts and blood vessels,

This may lead to a faster progression of the disease. Unlike teeth, there are different types of surfaces on implants.

Rough surfaces are apparently at a higher risk of developing peri-implantitis than smooth surfaces, from the moment they are exposed to the oral cavity.

However, no difference was found in the inflammatory process between the different surfaces6.

Risk factors

There are several risk factors for the development and progression of peri-implantitis, including poor oral hygiene16, cement residue, or other local factors17,18.

History of periodontal disease19-22, smoking19,24,25, genetic factors26, diabetes and occlusal loading27. Poor oral hygiene is the main cause of the development of peri-implant disease.

(Increases the risk of peri-implantitis 14.3 times). The anatomy of the implant and the restoration on it have a decisive influence on the patient's ability to perform optimal plaque removal,

and may constitute a risk factor for the development of the disease.12,16 In addition, mobility of the restoration parts, which may indicate loosening of the structure screw or the crown itself, may affect

The inflammatory condition around the implant, as the lack of connection between the implant and restoration parts is a potential site for bacterial colonization. Also, subgingival cement residues

Around implants, they may serve as both an inflammatory factor and a site for bacterial colonization, and have also been found to be a factor in the development of the disease17.

diagnosis

The diagnostic process includes a clinical and radiographic examination. The clinical examination includes measuring pockets around the implant and the radiographic examination includes a periapical radiograph.

Used to assess bone height. The tests are important not only for diagnosis, but also for monitoring the health of the tissues around the implant.

A diagnostic radiograph should be taken on the day of implant placement and then on the day of loading. The second of these will be the baseline photograph for monitoring the bone support of the implant,

Because it is performed after the initial physiological remodeling process that occurs around the implant12, 28. The common assumption is that bone loss that occurs after the initial physiological remodeling process

Physiological remodeling is the result of bacterial infection. 6. On follow-up examinations, when the clinician notices bleeding and/or an increase in the depth of the pockets around the implant,

Take an X-ray to check for bone loss around it.

Treatment

It is important to remember that, as of today, there is no treatment that constitutes a standard of care for cases of peri-implantitis, and further studies are needed to obtain a clearer answer.

The effectiveness of various treatments for this disease. This emphasizes the importance of prevention. Peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis are different diseases that require different treatment.

Peri-implant mucositis, unlike peri-implantitis, is a reversible disease5,29 and can usually be treated using a non-surgical technique12.

This treatment includes daily mechanical plaque removal and maintenance by a hygienist. Unlike peri-implant mucositis, the non-surgical treatment of peri-implantitis

It has been shown in most studies to be ineffective 12,30,31 and therefore requires surgical intervention using a flap lift (Surgical Open Flap Debridement- OFD).

Surgical treatment generally includes removal of granulation tissue and cleaning of the implant surface. As part of the treatment, bone resection or regeneration of the bony defect may be performed.

The decision whether to perform restorative or regenerative treatment depends on the aesthetic requirement at that site, the morphology of the bone defect, and the presence or absence of adjacent teeth or implants.

Surgical treatment has been shown to be more effective than nonsurgical treatment. Nonsurgical treatment may be limited in its effectiveness due to the anatomy of the implant and/or the structure and restoration on the implant12.

Non-surgical treatment using a jet with chlorhexidine gel – encouraging initial results

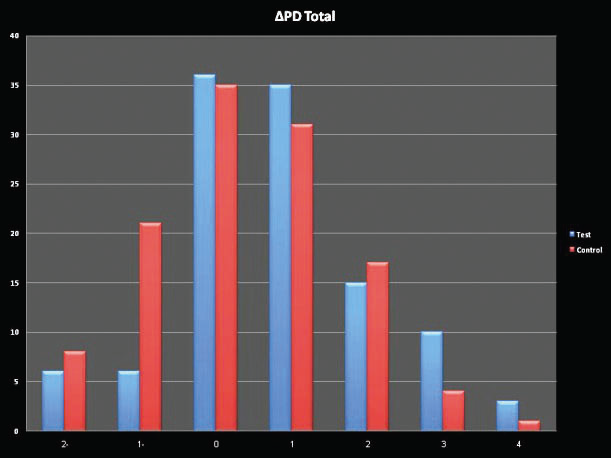

In a recent study, the effectiveness of the jet device in combination with chlorhexidine gel in the treatment of peri-implantitis lesions was examined32.

40 patients were tested and divided into a control group that received a maintenance, training, and follow-up session and an experimental group that also received a jet device.

In combination with chlorhexidine gel for daily home use. After 3 months, the condition was reassessed. At the reassessment,

A more significant decrease in pocket depth was found in the experimental group that used the jet device in combination with chlorhexidine gel.

The changes in pocket depth can be seen in graphs 1 + 2. In addition, a significant decrease in the number of bleeding sites was found in the experimental group that used

in the jet device in combination with chlorhexidine gel compared to the control group. It is important to note that the jet is not intended to replace proper and strict oral hygiene,

But to add an additional element of site disinfection. It is also possible that just as the jet helped treat lesions around implants, it also has a role in preventing such lesions,

Therefore, it would be recommended to add it to the basket of devices provided to patients in order to perform good maintenance of implants.

Graph 1 Change in average pocket depth after 3 months:

(taken from the article, Levin L, Frankenthal S, Joseph L Rozitsky D, Levi G, Machtei EE. Water Jet with adjunct Chlorhexidine Gel for Non-surgical Treatment of Peri-implantitis Quintessence Int. 2014;45:In press)

Graph 2 Change in the deepest pocket around the implant after 3 months:

(Taken from the article, Levin L, Frankenthal S, Joseph L Rozitsky D, Levi G, Machtei EE. Water Jet with adjunct Non-surgical Treatment of Peri-. Chlorhexidine Gel for implantitis. Quintessence Int 2014;45:In press)

To date, no effective treatment has been found for peri-implantitis. Until a specific treatment is proven effective, it is necessary to focus on preventing it, as this is the most effective treatment today.

Before we can perform implants, we must first perform comprehensive periodontal treatment while treating the systemic risk factors for the disease, and reach a state where there is no active disease in the oral cavity.

It is also necessary to inform the patient about the risk involved in implant treatment and how it can be reduced, while maintaining strict oral hygiene and reducing systemic risk factors.

such as smoking and diabetes control. The importance of routine and thorough maintenance for the long-term success of treatment must be emphasized. As with any inflammatory disease,

Early detection of the disease will lead to rapid intervention in its early stages and a better outcome. To this end, routine monitoring of implants is necessary as part of periodontal assessment and maintenance.33.

From magazine No. 19 Oct. 14 pages 46-47, see REFERENCES page 48